The following is reprinted from an article of the same name, with permission of the author.

Austin last took a hard look at its historic preservation program in the early 2000’s, where a joint task force made up of Planning, Zoning and Platting, and Historic Landmark Commissioners made some recommendations to upgrade but not fundamentally alter the city’s program as originally established by always serving ZAP commissioner Betty Baker in the mid 1970’s. Betty Baker herself chaired the 2003-2004 task force that was tasked with examining the question.

The time has come for Austin to do heritage preservation and management correctly. Piecemeal reforms applied over the years have not worked; we need a complete redo. As one of Austin’s leading African-American preservationists I offer my time and services toward the achievement of this objective.

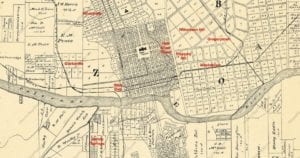

Map of Austin’s Urban Freedmen’s Communities, Circa 1900

Basic Background

At a time during the early to mid 1970’s when the full meaning of the National Historic Preservation Act and the National Environmental Policy Act was still being figured out, Baker advocated for and helped to successfully enact a historic preservation program in Austin that was fundamentally Southern and bourgeois in character and administration. It reflected an early post-Lyndon Johnson, Roy Butler-esque repudiation of the Great Society and embraced a more homespun Texan understanding of history and historical significance grounded in respect for private property rights. I should not have to say so but I am going to do it anyway: this was a program designed by white people to primarily benefit white people, just as the Austin “Gentleman’s Agreement” concluded just a few years prior had been. Austin’s African-American and Latino preservationists could get properties landmarked, but only at white ruling class discretion.

In doing so Baker was not being altogether unusual; what she put into place was an Austin version of what already existed in other cities of the former Confederacy such as Charleston or Savannah, already bourgeoning centers of a peculiarly Southern brand of heritage tourism that emphasized the quality of the fine china at plantation big houses and avoided discussion of the slave quarters. In examining this history it may be useful to bear in mind that First Ladies from Lady Bird Johnson to Laura Bush – and women like them at lower levels of government like Betty Baker – have played an important part in the politics of historic preservation over the years. Baker did not take as many cues from the preservation programs in place in Galveston and San Antonio, the two Texas cities generally judged at the time to have the “most history” because some of the history in those cities was more complicated.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of what Baker established in Austin was the program’s misguided over-focus on historic buildings. This imprudent attention has led to the compromise or destruction of dozens of non-architectural historic properties in Austin, some of them of considerable research value. In 2017 it is fair to say that when Austinites think of “historic sites” they nearly always think of historic buildings, not archaeological sites or Traditional Cultural Properties, although the latter two are also historic properties eligible for National Register consideration and historic landmarking. The excessive attention paid to historic buildings is, of course, a sign of white middle and upper class bias; members of minority groups and the working class have rarely occupied grand estate homes whose “historic” character is obvious to the untrained eye. City staffers at this stage don’t even bother to meaningfully pretend that they care about anything other than historic buildings; the recently completed East Austin historic resources survey was not only strategically gerrymandered to exclude much of East Austin as well as Montopolis, Dove Springs and Del Valle, it only focused on buildings, not archaeological sites or TCP’s.

Another aspect of Baker’s legacy is the stringent requirement for landmarking historic districts. It is notoriously difficult to establish historic districts in Austin due to a requirement that at least 51% of property owners in the proposed district agree to the zoning change. The former Austin Historic Preservation Officer weighed in publicly about that in 2004; it was a major factor in why she left her position and was replaced by her assistant Steve Sadowsky. Here’s the truth: in most American cities historic zoning is conducted like any other type of zoning. Special districting requirements such as Austin’s are unusual and are usually enacted at the behest of real estate interests and private property rights fundamentalists.

What is now clear over forty years later is that Austin’s historic preservation program has become inequitable, one-sided, and unfair. It not only subsidizes the preservation of an elitist conception of the city’s history, the program also buttresses city-driven practices of gentrification. In short, a program that should be protecting the heritage of every culture in our city is instead administered in keeping with the cult of minimally regulated real estate development that has characterized the recent history of our city. In doing so, our city’s leaders are not only violating the spirit and letter of historic preservation laws and violating basic standards of professional practice, they are engaging in deliberate acts of institutional racism. What is also problematic is this: Austin’s minority taxpayers are subsidizing tax breaks for rich West Austinites and are not seeing their own history adequately reflected in Austin’s landscape.

In this presentation I made two years ago before the Austin Human Rights Commission concerning the Rosewood Courts historic zoning case, I pointed out some of the hypocrisies and racial inequities in the city’s historic preservation policies and practices. I could elaborate on them with further quantitative and qualitative data–further discussion of the role of real estate development (and Betty Baker) in the destruction of Clarksville in particular–but in the interest of saving time and space I will now focus on what I see as the most important fixes our city should undertake in order to satisfactorily reboot our city’s historic preservation program. I also encourage you to read or re-read my February 7, 2017 blog post in which I offered preliminary reform remarks in the wake of the most recent audit of the historic preservation program.

Basic Principles

- Race and Class Equity and Fairness

- Democracy, Public Transparency and Accountability

- No Special Interest Favoritism

- Ease of Use

I elaborate on each principle in turn:

Austin’s historic preservation mismanagement has been willful as well as harmful. Thanks to people such as Betty Baker and her progeny such as Jerry Rusthoven, the race and class snobbery has been baked into the cake. A basic sense of integrity, fairness and commitment to the truth demands that a sense of restorative justice be institutionalized into how Austin conducts heritage management going forward. In practice this means conducting proper eligibility studies of ALL of Austin–and for all eligibility categories, not just buildings–with a special focus on East Austin, in collaboration with bona fide neighborhood organizations. Imagine Austin must also be amended to better reflect East Austin values. Our cultural resources matter just as much as our natural resources.

The Austin City Council needs to make it clear to the city’s real estate interests that their hegemony over our city’s historic preservation practices must end. This means fundamental reforms to how appointments are made to the city’s historic landmark commission–lawyers or real estate agents with no credentials in historic preservation have no business on that commission–and rigid adherence to the National Register procedures the city claims to follow. In most cities members of the Landmark Commission are experts in the field of historic preservation, not political hacks with axes to grind such as former Austin commissioner Arif Panju. The federal manual for National Register State Review Boards specifically states as follows:

BEYOND THE INTRICACIES OF HISTORIC JUDGMENT, OTHER IMPORTANT ISSUES FACED BY THE REVIEW BOARD ARE THE POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC RAMIFICATIONS OF NATIONAL REGISTER LISTINGS. A PRESENT OWNER MAY OPPOSE A PROPERTY’S LISTING REGARDLESS OF ITS SIGNIFICANCE, BECAUSE OF A FEAR OF BEING UNABLE TO DEVELOP OR USE THE PROPERTY AS DESIRED. ON THE OTHER HAND, AN OWNER MAY PUSH FOR NOMINATING A PROPERTY THAT DOES NOT HAVE SUFFICIENT HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE TO JUSTIFY LISTING IN ORDER TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF CERTAIN TAX INCENTIVES. THESE FACTORS SHALL NOT BE TAKEN INTO CONSIDERATION BY THE STATE REVIEW BOARD. THEIR RESPONSIBILITY IS TO APPLY PROFESSIONAL, TECHNICAL STANDARDS IN AN UNBIASED FASHION TO DETERMINE IF PROPERTIES MEET THE NATIONAL REGISTER CRITERIA.

This is what Austin’s Historic Landmark Commission also ought to be doing. Staff ought to be helping them do so, not playing political games and shilling for real estate developers at taxpayer expense, as Jerry Rusthoven slimily did for Austin Stowell at the Montopolis Negro School or for the Austin Housing Authority in the Rosewood Courts case. Austin’s Historic Landmark Commission should also reflect the diversity of Austin; it is unconscionable for this commission to continue to be without qualified African-American representation for as long as it has, especially while it deliberates over and decides highly controversial cases involving sensitive African-American cultural heritage.

It also means finally adopting and enacting the historical wiki that city officials have let sit on the shelf for years in beta status. Every citizen of Austin ought to be able to easily find out where the historic properties in our city are located using a tool such as Google Maps, developers included.

- It’s not just real estate interests. Preservation Austin and similarly bourgeois advocacy groups are part of the problem and must undertake democracy-enhancing accountability reforms inside their own organizations. They can become part of the solution if they concede the role they have played in perpetuating institutional racism in our city and commit to relinquishing some of the oppressive prerogatives they have garnered over the years, most of which are rooted in their incestuous relationships with developers and Austin’s real estate interests. One concrete step Preservation Austin could take is to cease its advocacy for CodeNEXT. CodeNEXT would be a disaster for East Austin in particular and would destroy much of its cultural heritage.

In many ways the organization now known as Preservation Austin is as much a creature of Betty Baker as the city’s historic preservation program itself. The organization can send the message that it cares about true and equitable historic preservation by advocating for the proper protection and care of working class and minority cultural heritage alongside or in support of bona fide minority led and controlled historic preservation organizations such as the Burditt Prairie Preservation Association. - Historic Preservation is not hard. Its basic public policy framework is straightforward. Yet the Great Society that established much of how “cultural resource management” is presently conducted was targeted by Governor George W. Bush’s deregulatory hitmen starting in the 1990’s for relatively simple reasons: if not administered correctly, the requirements of Section 106, NEPA or the National Register can be stereotyped as needlessly bureaucratic, even oppressive, especially by real estate developers and other special interests. The framing of this issue as one of excessive regulation was always a political canard.

- Democracy matters. Historic preservation need not and should not become the personal playground of insiders and specialists making unaccountable decisions in the dark. Ease of use means that public employees should conduct themselves with a devotion to duty that reflects the customer service and public education ethos lying at the heart of heritage preservation. Public heritage managers must also have the political courage to enforce the independent analysis of cultural properties; it is a fundamental conflict of interest to permit developers to hire their own for-profit historic preservation consultants. Cultural Resource Management guru Tom King has written and spoken cogently about some of this over the years.

In closing, I need to re-stress the following: minor technocratic fixes are not going to get the job done. Recent advocacy efforts concerning the Montopolis Negro School and the Hotel Occupancy Tax (a.k.a. HOT Tax), are indicators that fundamental historic preservation reform enjoys broad citizen support and cannot be pushed further down the road. Too much heritage has already been lost, and further controversies surely await if we fail to promptly act. The inequitable Betty Baker approach to Austin historic preservation has gotten us this far, but the time has come to turn the page; we need a historic preservation program for the 21st century: one that is inclusive, ambitious, comprehensive, collaborative and democratic.

Worthy Examples

I am limiting my list of more or less exemplary cities to the United States. As a German I am tempted to point to what I consider to be worthy European examples, but my list is invariably constrained by a basic American fact: the United States is the only major country on earth to consider cultural heritage to be private property instead of part of the public domain, something routinely discussed at UNESCO over the years. In fact in states such as Texas even human remains are considered to be private property if located on private land or water.

Should the Austin City Council convene a new task force to advise it on fundamental historic preservation reform, here are some cities worth looking at:

- Seattle’s historic preservation program is housed inside the city’s Department of Neighborhoods and since 2000 has endeavored to undertake a comprehensive analysis of historic properties inside the city’s limits. Austin can learn many lessons from this effort, good and bad.

- The Boston Landmarks Commission is one of the most qualified and highly regarded bodies of its type in the United States. It doesn’t always come down on the side of preservation, but its deliberations are usually well grounded and based on empirical–and properly documented–evidence, including archaeological and cultural landscape analysis.

- The San Antonio Office of Historic Preservation does it far better than Austin does. The office is properly staffed with qualified professionals, and they get to do their job without some developer’s stooge constantly breathing down their neck. The main reason they can do this is because the department’s chief administrator reports directly to the city manager, not to the city’s planning and zoning director.

About Dr. Fred L. McGhee

Fred L. McGhee is an historical archaeologist and urban and environmental anthropologist. One of the leading scholars of the African Diaspora in the United States, he is founder and president of Fred L. McGhee & Associates, the only Black and Disabled Veteran owned and operated consulting company of its kind in the United States. He is the author of numerous publications on diverse subjects such as slave ship archaeology, Afro-Texas history, modernist architecture, residential energy efficiency, language acquisition, Black American Sign Language, German colonialism, the African Diaspora in Hawai’i and the Pacific, public housing history and architecture, home-birthing and other topics. Some of his writings are available at his Academia.edu page, as well as in the pages of the Austin Chronicle and the Texas Observer. For more information, see fredmcghee.com.